Foreword: Vietnam A Century Past, Nguyễn Tường Bách and I are the titles of two memoirs authored by Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách and teacher Hứa Bảo Liên, his lifelong companion respectively. These two outstanding works record the romantic love between a young Vietnamese gentleman and a Chinese lady in Hanoi. The eventful politics of the country drew them apart until the day their paths again met in Kunming, Yunnan and united them in lasting matrimonial bliss that entailed much devotion and sacrifice – but more importantly, their lives reflect the history full of upheavals and vicissitudes of the Revolutions that engulfed both Vietnam and the Chinese mainland.

Picture 1: left, Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách; right, teacher Hứa Bảo Liên during an interview with Lawyer Lâm Lễ Trinh, on 09.24.2005. [source: Little Saigon TV, Picture by Đinh Xuân Thái] [6]

BIOGRAPHY

Nguyễn Tường Bách saw life on March 26, 1916, at Cẩm Giàng a small district in Hải Dương Province. However, two generations prior, his ancestral family moved from Cẩm Phô Village, Điện Bàn district, Quảng Nam Province to the North. The Nguyễn Tường family had seven siblings: Nguyễn Tường Thuỵ, Nguyễn Tường Cẩm, Nguyễn Tường Tam – Nhất Linh, Nguyễn Tường Long – Hoàng Đạo, Nguyễn Thị Thế, Nguyễn Tường Lân – Thạch Lam, and Nguyễn Tường Bách – Viễn Sơn.

THE EARLY YEARS – MOVING FROM CẨM GIÀNG TO HANOI

Nguyễn Tường Bách started elementary school in Hải Dương, then Thái Bình, to end up at the Hàng Vôi School in Hanoi. He attended the Bưởi High School for a time before quitting because he did not agree with its French colonial administration. He stayed home and self taught with text books he purchased then took the examinations. He passed the Baccalauréat I but not the Baccalauréat II for failing to study some of the required subjects. Nguyễn Tường Bách went back to formal schooling at Albert Sarraut High School then passed the Baccalauréa II in Philosophy with High Honors. Born an artist, Nguyễn Tường Bách decided to forego medical training he considered boring but eventually enrolled with the Medical School in Hanoi on the advice of his family... [6] Seven years later, in 1944, he graduated as a medical doctor with Outstanding Honors. His classmates included: Dr. Vũ Văn Cẩn (Health Minister in Hanoi), Đặng Văn Chung (Professor of Medecine), Nguyễn Trinh Cơ who decided to stay in North Vietnam and Dr. Trần Đình Đệ (Health Minister in Saigon), Nguyễn Đình Cát (Professor of Medecine), Nguyễn Đình Hào who moved to South Vietnam in 1954.

Younger generations probably know Nguyễn Tường Bách only as an elderly revolutionary but fail to see in him a very playful young Nguyễn Tường Bách. In spite of being already a medical student, each time he went back to the family ranch at Cẩm Giàng for New Year visits, he always showed himself the happy go lucky, playful “Chú Bẩy/ Brother Seven” - he’s the youngest child in a family of seven siblings - that he was. His niece Nguyễn Tường Nhung, daughter of writer Thạch Lam, painted him with this lively brush:

“The time we lived at Cẩm Giàng ranch with paternal grandmother, Uncle never failed to show up during the holidays, Tết or anniversary celebrations. He was easy going and joked around with the nieces and nephews. Grandmother would tell him to bring the votive items to the grave of “cụ Huyện bà”, at the foot of an ancient banyan tree with a canopy that spread out in a circular shape looking like a tray. The people in the village called it “cây đa Mâm Xôi” or “the tray banyan tree”, not very far from the ranch. The offerings usually consisted of: sticky rice, boiled chicken, flowers, fruits, incenses, and man-size paper figurines, money, clothes, hats for the worship of the Spirit of the Earth. All those things were made of very beautiful, shining paper in five different colors. As soon as we left the ranch behind, Uncle playfully put the hat on his head, distributed the offerings to us kids and we followed him in a procession singing to our heart’s content. Our task was to bring the offerings to the grave of “cụ Huyện bà” but we did not have the slightest idea about her. We only knew that she was called “cụ Huyện bà”. We had no idea about the year of her passing except that her anniversary fell on the fifth of January of the lunar calendar. My paternal grandmother came from the Central region. She was extremely strict in matters of ancestor worship. Food reserved for offering could not be tasted during preparation. Therefore, it was taxing on the skill of the cooks who were usually the daughters in laws or daughters of the family. Several days before the anniversary celebration, only aunt number Five (Mrs Nguyễn Thị Thế, the mother of Duy Lam and Thế Uyên – notes by the author) showed up to give my mother a hand in the preparation. The daughters in law in Hanoi only sent dry food like mushrooms, swim bladders/ fish maw as contribution to the event etc...The aunts in law only came one day before the celebration. Meantime, for the whole week, my mother had to wake up at four or five in the morning to take care of everything like cleaning, soaking the dry food in water, assigning tasks to the helpers to shine candle holders, incense burners, clean the house, tidy up the garden. The activities around the ranch became markedly animated. Father arrived with my sisters and brothers. I was excused from school. The sisters played with each other while the brothers often fooled around in the garden or ran to the fields. The food displayed on the altar could only be taken down after three burnings of incense that took approximately two hours. We might be hungry, but everybody must wait for the offerings to be taken down before we could eat. There were certainly a lot of food left in the kitchen, but grandmother saw to it that nobody could eat while the offerings were still displayed on the altar. On that particular occasion, uncle led us into the altar room, signaling us to walk silently. He took the sticky rice plate down, turned it upside down then started to pull out the rice from the underneath leaving its shape intact. He gave each of us rice balls the size of a chicken egg. Naturally, our hunger was in no way assuaged but we took great fun in thinking that grandmother had no inkling about our mischief.” [excerpt from the memoir Tháng ngày qua/ The Days Past by Nguyễn Tường Nhung]

Picture 2: The lacquer work Trước Cơn Giông/ Before the Storm by revolutionary / painter Nguyễn Gia Trí depicting the ancient banyan tree with a spread out foliage in the shape of a tray the people in the village called Cây Đa Mâm Xôi. [private collection of Nguyễn Tường Giang]

Nguyễn Tường Bách graduated from medical school but chose a different path in life – using his pen to fight! Early in his youth, in the footstep of Nguyễn Tường Tam – Nhất Linh, Nguyễn Tường Long – Hoàng Đạo, Nguyễn Tường Lân – Thạch Lam his older brothers, Nguyễn Tường Bách joined the staff of the two papers Phong Hoá and Ngày Nay, the mouthpiece of Tự Lực Văn Đoàn, wearing the many hats of journalist, writer, and poet. After the death of his older brother Thạch Lam (1942), Nguyễn Tường Bách took over the management of the printing shop and the paper Ngày Nay. The seven members of Tự Lực Văn Đoàn at that time included: Nhất Linh, Khái Hưng, Hoàng Đạo, Thạch Lam, Tú Mỡ, Thế Lữ, Xuân Diệu, absent Nguyễn Tường Bách. It could be said that Nguyễn Tường Bách belonged to the generation of medical doctors in the 1940s who ventured, at an early stage, into the field of journalism and art.

Very early on (1939), Nguyễn Tường Bách got involved in politics. He joined the Đại Việt Dân Chính Party along with Nguyễn Tường Tam, Nguyễn Gia Trí, Trần Khánh Giư / Khái Hưng, Nguyễn Tường Long / Hoàng Đạo… during its evolutionary course, Đại Việt Dân Chính merged with Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng (1943), Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng then merged with Đại Việt Quốc Dân Đảng under the new common name Quốc Dân Đảng (1945).

In March, 1945, after the Japanese coup against the French, Nguyễn Tường Bách still served as director of the paper Ngày Nay with the collaboration of Hoàng Đạo, Khái Hưng…[2]

August, 1945, the Japanese surrendered, the Việt Minh seized power, the Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng and Cách Mệnh Đồng Minh Hội parties went public. Nguyễn Tường Bách served as central committee commissioner, in charge of the party organization and its propaganda arm, published the paper Việt Nam Thời Báo later renamed Việt Nam, the mouthpiece of Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng that openly opposed the policy of the Communist Party. During that time he also founded the youth group Quốc Gia Thanh Niên Đoàn.

The situation was extremely critical, ripe with adversities. The Việt Minh and nationalists constantly clashed. Each time Nguyễn Tường Bách went out he had to be accompanied by bodyguards. He worked day and night at the newspaper’s office. In May, 1946, events took an unfavorable turn. Under the terrorist threat from the Việt Minh, Nguyễn Tường Bách and his comrades left Hanoi for the war zone – Đệ Tam Khu of the VNQDĐ, to carry on the struggle.

Đệ Tam Khu was a pretty large region encompassing Vĩnh Yên to Lào Cai. At this location, Nguyễn Tường Bách assisted the party leader Vũ Hồng Khanh in running the military command (according to Nguyễn Tường Thiết, Vũ Hồng Khanh graduated from the Huangpu Military School). The VNQDĐ only controlled the cities while the rural areas were in the hand of the Việt Minh who continuously surrounded and attacked Đệ Tam Khu. In order to preserve its forces, the VNQDĐ, withdrew to Việt Trì, then Yên Báy, Lào Cai. In the end, the Party Central Committee of the VNQDĐ ordered Vũ Hồng Khanh to stay at Đệ Tam Khu, while Nguyễn Tường Bách to move to Kunming and handle the overseas affairs.

THE PERILOUS JOURNEY

August, 1946, a group of eight people including Nguyễn Tường Bách departed from Lào Cai then crossed the iron bridge straggling the Nam Khê River to set foot in Hà Khẩu / Hekou – an autonomous territory of the ethnic Dao, the gate to south Yunnan Province, China. Yunnan covered an area larger than that of Việt Nam. The only baggage each of them carried was a “túi dết” – a large canvas bag - marking the start of a more than 40 years long life in exile [1946-1988] for the Vietnamese young man Nguyễn Tường Bách, in China, a land engulfed in a tumultuous war.

The 1,500 km long trek from Hekou to Kunming was arduous. As a result of the Sino-Japanese War, most of the railroad tracks were destroyed and they had to walk on foot the majority of the time. Those young men had to negotiate mountain passes, wade streams, cross rivers, climb mountains, descend into valleys, traverse steppes, enter many hamlets of ethnic minorities: the Hán, Mán, Hui – Chinese devotees of Islam, and at times Vietnamese expatriates who have settled in the land since time untold.

They walked by day, rested by night, sought refuge at unfamiliar houses. Mindful of insecutiry, they had to take turn standing guards for the group to sleep. The next morning, they continued on their journey. At parts of the way, they joined pack horse caravans but danger always lurched around the corner at the hand of bandits or military renegades eager to rob or kill.

“The frightful scene on the side of the road, in a cave a curled up corpse, they were greeted by a skeleton still dressed in its tattered clothes, a straw hat lying at its side…” [3]

After a long march they eventually arrived at a railroad track but learned that the area ahead was flooded and there was no way to tell when the trains would run again. They could not wait and the only choice was to move on along the tracks knowing full well that the coming days would be extremely strenuous. They were told by the people in the village even in the best of conditions it would take 4 to 5 days for them to reach Pingbian before they could reach the main road leading to Mengzi.

With their youthful confidence, they chose the hard way without knowing what was awaiting them. Narrow paths must be negotiated, steep cliffs climbed,

They held on tree roots to negotiate each step of the way upward, cut elephant grass at places, fell trees to clear the path. Near exhaustion, several days later, the group set foot into a mountainous region of gradually lower elevation. From there, they left the highlands to descend into the plains.

At last, they reached Pingbian, the first main stage of their journey. The next day, the eight “travelers” had to get up early to string along a caravan of pack horses heading toward Mengzi – a landmark famous for its peaches. From there, they could board a train to Kaiyuan, the site of a Việt Quốc cell. However, each of them was anxious to get to Kunming soon. [Picture 3]

Picture 3: left, [location of the numbered landmarks on the map] the journey on foot by Nguyễn Tường Bách and the 7 “travelers” starting from (1) Lào Cai to (2) Hekou, (3) Pingbian, (4) Mengzi, (5) Kaiyuan, (6) Kunming. [source: The Contemporary Atlas of China (Boston : Houghton Mifflin Co., 1988), p. 31.]; right, section map of Vietnam and China and the area of operation of Nguyễn Tường Bách and VNQDĐ Overseas Office/ Hải ngoại vụ VNQDĐ: Kunming – Yunnan Province, Guangzhou – Guangdong Province, Hong Kong, Shanghai.

The young urbanite Nguyễn Tường Bách, recent medical school graduate in his late twenties, found himself subjected to the ordeal of going on a grueling journey of over 1,500 km long. Looking at each other, they only saw emaciated and sun burnt bodies. On the platform of the Kunming Rail Station, the group was greeted by Nguyễn Tường Tam, Nguyễn Tường Long, Trần Đức Thi, Xuân Tùng and the various members of the local party committee. In particular, the young Chinese lady Hứa Bảo Liên who was then studying the Humanities at Yunnan University.

It was such a “wonder”, a fateful coincidence Hứa Bảo Liên called “predestined love,” that the two friends again met. At the close of 1946, Nguyễn Tường Bách and Hứa Bảo Liên exchanged matrimonial vows in Kunming – the City of Four Springs.

“We met on this strange land quite coincidentally. This swift encounter forced me to think sometimes one just needs to take a different turn then one’s life would be completely different … At the end of the year we became husband and wife in a very simple ceremony with no formalities not even a wedding ring. We bravely slogged ahead toward an uncertain future with faith in each other as our only bag and baggage.” [5]

In the Second World War, Kunming was decribed as “a small slumbering, isolated Oriental town” by the legendary air force general Claire Chennault of the Flying Tigers Squadron stationed there.

In fact, Kunming never proved to be a safe haven for the Vietnamese revolutionaries because the French still retained some degree of influence locally. They still kept a consulate there and their security apparatus was keeping a close eye on the anti-French acitivities of the Vietnamese revolutionaries in order to sabotage, weaken, or buy them over. Moreover, the French hospital Paul Doumer was still in operation. Nguyễn Tường Bách wrote:

“A strange thing. Somebody had the intention to recommend me to work as a medical doctor at that hospital. Several of my classmates from the Hanoi Medical School worked there. It’s odd to think of it. Were I a different person I could have gone to work there. A comfortable life in a placid environment.” [3]

That prospect of wealth was within his reach. However, it could not entice the young Nguyễn Tường Bách who was resolved to engage in the arduous path of a revolutionary decribed by the poet Thế Lữ:

A warrior am IOver perilous land and sea travel

More than anybody, Nguyễn Tường Bách realized that though Kunming served as a base of the Vietnamese Revolution it was only a temporary stop leading to the next stage. The immediate objective of the VNQDĐ’s Overseas Office in Kunming was to gain the support of the Chinese Kuomingtan for the liberation of Vietnam. How long would such endeavor take was impossible to predict.

THE CHINESE YOUNG GIRL OF THE HÀNG BUỒM ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

Hứa Bảo Liên was born on the 4th of August, 1925 to Chinese parents. She saw life and grew up in Hanoi. Her father, a rich head of a Chinese Association, had a business and second family in the city of Nam Định. Bảo Liên spent her youth with her mother and grandmother. When she reached school age, her mother sent her to the Chinese Hàng Buồm elementary school. Liên loved to go to school and in spite of being a girl, enjoyed sports especially ping pong. She won many prizes and trophies cluttered her home.

Her mother was totally devoted to her and loved her classmates who in turn called her “mom.” Famous teachers from Hong Kong and Guangdong were lured to come and teach at her high school. As the Japanese invaded China, a number of intellectuals holding college degrees sought refuge in Vietnam, particularly Hanoi and came to teach at her school. Later on, Hứa Bảo Liên found out that several of them were members of the Kuomintang and Communist Party.

The students were taught in the spirit of Scouts with strict disciplne. The teachers introduced in the curriculum the campaign “new life” from China. It promoted a sane way of life, rejection of the feudal old-fashioned ways, equality of the sexes, even acceptance of homosexuality. The school library constantly received many books dealing with modern thoughts, works by famous authors like Lu Xun, Ba Kim/ Li Yaotang … that political environment helped shape the way of thinking as well as the liberal, independent, and strong personality of Hứa Bảo Liên later in life. Especially after the death of both her mother and grandmother. The time she spent daily at her mother’s beside made the youthful Hứa Bảo Liên a familiar and well liked fixture at the Phủ Doãn Hospital.

Liên lived by herself after her grandmother and mother’s passing. On Saturday afternoons or during the holidays, instead of staying home or going out, the scout in her urged her to volunteer at the Phủ Doãn Hospital. She was allowed to accompany the medical doctors during their visiting routes. Sometimes, she took her meals and played ping pong at the hospital until the evening. It was on those occasions that Hứa Bảo Liên and the medical student Nguyễn Tường Bách met.

The Sino-Japanese War spread. Hứa Bảo Liên, still a minor, fervently joined anti-Japanese groups. However, when the Japanese advanced into Indochina, all organizations were dissolved. Only a clandestine few continued to carry on their anti-Japanese activities. Japanese was added to her school curriculum. Summer 1945, under such unusual circumstances, Hứa Bảo Liên graduated along with 13 of her classmates.

Another noteworthy development: August, 1945, Hứa Bảo Liên won the “North Vietnam champion” award in ping pong. Her opponent was a Vietnamese female player who later represented the Vietnamese ping pong team on a tour of China.

ABOUT THE PHỦ DOÃN HOSPITAL

Hứa Bảo Liên wrote: “By fate, this hospital played an extraordinary role in my life and exerted a deep influence on my future. Much happiness and sorrows, death and grief came from that place. Rain or shine this period remained forever in my mind because it was a decisive time for me. The surprising thing was when I visited the hospital to care for my dear ones or countless other patients, the medical doctors and nurses all showed their sympathy for me – a little student in her teens, innocent, honest, sincere and appreciative of the people who did their best to treat her mother. In my eyes, they were my good friends, fathers, uncles and siblings who were precious to my heart and cared for me during my most trying, lonely and lost times in life.”

A Chinese girl who out of the blue became a member of the big family at that hospital. In 1942, 1943, besides my school hours, on my spare time, I would go to the hospital on weekends or holidays to be with the staff. On top of being a hospital, it was the place where medical students received their training. I felt very happy when I was given special treatment to accompany the medical doctors on their visiting routes even though the reason for it totally escaped me.

The medical doctors gave me a white gown so that I could play the part of a student but nobody was fooled because I stuck out like a sore thumb standing in a group of medical students. Some people would stare at me when they saw me entering the patient’s room side by side with the medical doctors at the head of the group. At times, doctor Huard would lead the pack of mostly male medical students and a few female ones. The students did not know my place in their group, they wondered if I was the relative of a medical doctor and they often teased me by asking: “What class are you with? When are you going to graduate?” I put on a serious face then replied: “I’m on my 9th year, about to graduate. Even before you.” I was not telling lies because I actually attended the 9th grade at my Chinese High School. There were occasions when I would join the medical doctors at the cafeteria. After dinner, I often played doubles: I and Dr. Tùng (Tôn Thất Tùng) would form a team while Dr. Tâm (Phạm Biểu Tâm) and Dr. Cơ (Nguyễn Trinh Cơ) would play opposite us … Often it was our team who had the upper hand.

At the time I looked up to Dr. Tùng (Tôn Thất Tùng) as my godfather. He paid a lot of attention to my schooling. He had in mind a plan for me: Upon graduation from the Chinese High School I would study French for three years. After that, we would look for opportunities for me to enroll in medical school. Unexpectedly, events developed fast. The Japanese troops occupied Vietnam, my plan for a medical career went up in smoke.”

The names of well-known physicians at Phủ Doãn Hospital at the time were listed by Hứa Bảo Liên in her book: In addtion to Dr. Tôn Thất Tùng, Phạm Biểu Tâm, she added Dr. Hồ Đắc Di, Nguyễn Xuân Chữ. Doctor Huard – the well respected giant in the medical world of both the North and South was also mentioned.

“Doctor Huard* the French professor at the Medical School also served as the head of surgery department at the hospital. Though he was the most respected physician there, he never failed to shake my hand and exchanged some pleasant words with me each time we met...I still remembered, near the end of 1945, Mr. Huard rode his bycicle to work and was brutally assaulted by an angry mob because the people rose up and attacked the French nationals to assuage their anger. His face was covered with bruises and his clothes were all torn up.” [5]

*Pierre Huard (1901-1983), the last French professor of the Hanoi Medical School, has trained many outstanding generations of Vietnamese medical doctors like Tôn Thất Tùng, Phạm Biểu Tâm... The irony of history saw to it that after the battle of Điện Biên Phủ (1954), Professor Huard became the representative of the French government and the Red Cross while Dr. Tôn Thất Tùng – his student represented the Việt Minh. Teacher and student worked together, from opposing front lines, on the prisoner exchange process.

End of 1942, Hứa Bảo Liên met Nguyễn Tường Bách the surgery trainee at the hospital. He graduated two years later. So, when they first met, he was already in his fourth year at the school at the age of 25. Their relationship – or more accurately love – probably began to bloom during that time. Nguyễn Tường Bách, also showed a predilection as a writer, journalist and poet. He earned a reputation with his short story “Tha Hương” that appeared on Giai Phẩm Xuân Đời Nay 1943 that in turn made him the idol in the hearts of many a female acquaintance.

Summer 1943, Hứa Bảo Liên and her school friends were arrested by the Japanese Kenpeitai and held in the basement of the Ideo printing shop on Tràng Tiền Street. The news of the disappearance of a number of the students at the school - the majority of whom were underage - shocked the Chinese community. After numerous demarches and also the desire of the Kenpeitai to gain the good will of Chinese associations, the students were released. A year later, the situation in Hanoi completely changed with the appearance of Chiang Kai shek’s troops on the scene.

Nguyễn Tường Bách felt utterly disturbed at the news of Hứa Bảo Liên’s arrest. He finally met her again after several months of detainment. The two were overwhelmed with joy. They were like two people sharing the same fate, the same aspirations. In spite of his heavy schedule at the medical school, the paper and “Secret Society” – terms used by Hứa Bảo Liên, Nguyễn Tường Bách still found time to help Liên catch up with Mathematics and French for the time lost because of her captivity.

And, her instincts told the girl that something has changed in the friendship or relationship between the two of them. They came to the serious decision of joining their destiny together regardless of the many challenges that lied ahead they needed to overcome, the opposition raised by the Nguyễn Tường family, the ethnic barriers. In those days not many Chinese women took a Vietnamese husband. It was in the summer of 1945.

A HANOI IN MOURNING 1945

After the Japanese’s coup against the French, the political situation became exceedingly tense. The Americans bombed Hanoi and other cities in the North. Alarm sirens blared at top volume. The Hàng Da Market was hit, a great number of people lost their lives or were wounded. Hứa Bảo Liên remembered:

“The victims were brought to the Phủ Doãn Hospital on stretchers. They formed long line extending from the gate to the operating room – 50 to 60 meters long. I saw with my own eyes people breathed their last before their turn to be operated upon! In the operating room, next to the hallway, bodies everywhere. Some were still living – others dead. The hospital staff was exhausted not knowing when their work would be over.”

Then, this is her recollection of the famine in the year of the Rooster 1945:

“Not long after, the news of a great number of peasants who died of famine reached me. The inhabitants of Hanoi started to notice emaciated bodies wandering aimlessly on the streets. Under extreme hunger, they stole food from street vendors. The number of beggars swelled. Every morning I saw oxcarts rolling down the streets to pick up cadavers. After a prolonged hunger, they shrunk and became lighter. They were covered with mats and piled up on the tiny carts to be transported to the city outskirt and buried.”

In those days, Hứa Bảo Liên lived in Hanoi. After her graduation, she taught at Chinese schools: one in Ngõ Gạch and the other in Hàng Than. At night, she translated Chinese news into Vietnamese or wrote commentaries on woman issues for Bach’s paper Ngày Nay. The heavy workload kept her occupied but she felt happy she was sharing the same aspirations with Bách. Bảo Liên led an independent lifestyle: A healthy body in the white blouse and blue skirt of her student uniform, no makeup and confident in her destiny. To build a better future, she intended to attend a Chinese university. She headed to Nam Định to obtain the consent from her father. Before embarking on the long trip, Bảo Liên paid a visit to the tombs of her grandmother and mother and went to see the couple Long Hoàng Đạo. She then headed to Việt Trì by car, hitched a ride on a boat to the war zone to see Bách to let him know of her plan to study in China. The two of them did not know when they would meet again. July 7, 1946, Hứa Bảo Liên bid farewell to Hanoi not knowing that it was the last time she would see the city.

THE PERSONAGES OF THE TIME

In 1943, Nguyễn Tường Bách took the eighteen year-old Liên to the editorial office at 80 Quan Thánh to meet anh Long also known by his the pen name Hoàng Đạo. Half a century later, Hứa Bảo Liên described the paper Ngày Nay in the following words:

“The office of Ngày Nay sat on the right side at the head of Quan Thánh Street. It was guarded by an iron fence, flower trees crowded the front yard including bushes of yellow bamboos. The printing shop and administration team occupied the ground floor where a group of workers was hard at work at the huge printing machines emitting rhythmic humming sounds, the smell of oil permeated the whole room. Upstair was reserved for the editorial staff. As you reached the upper floor you were greeted by a spacious living room doubling as a meeting space. At the center, several desks made up the working area while Khái Hưng’s private office was on the right.

Bách was engaged in a conversation with a man standing by a table. He was in his fourties, high nose bridge, deep eye sockets, bushy eyebrows. Bách introduced us: “This is miss Liên, and this is Long.” With a bright smile Long asked me to sit down. He was of average height, radiant eyes. At first sight, you would not tell that he was an effusive, unbiased person. I wondered whether he asked himself why his younger brother had such a young friend? In his jovial way, he inquired: “Do you like to read novels?” “Yes, I like to read Chinese and Vietnamese novels. My mother used to buy the magazine Phong Hoá. Then, I was most attracted to the comic section, humorous drawings as well as the dialogues between Lý Toét and Xã Xệ.” He smiled then asked about my schooling and activities. Before I left, he autographed a book for me and joked “This signature will one day be worth a fortune!”.

Hoàng Đạo (born 1907) He was only 36 then. Only 5 years later in 1948, Hứa Bảo Liên and Nguyễn Tường Bách exchanged the final vow and the couple lived with limited means at Bạch Hạc Động, a suburb of Guangzhou. It then fell on Bảo Liên the sister in law to look around to borrow from a friend HK$ 500 so that Tam, Bách and the other comrades could go to the Thạch Long Rail Station and take care of the burial of Hoàng Đạo who met a sudden death at the age of 42.

“Nguyễn Gia Trí had a full beard. At the time he lived with Bách, he made frequent use of paint cans and egg shells. Probably for that reason, even though a painter, he did not like to dress up. More often than not, people would see him in casual clothes wearing a pair of old rubber sandals. Miserly in speech and a straight in talk. He seemed not to mind what was happening around him and avoided to get into contact with others.”

Nguyễn Gia Trí (born: 1908), was 35 then, 8 years older than Nguyễn Tường Bách. Hứa Bảo Liên succeeded in painting a quite faithful portrait of the artist. A revolutionary member of the VNQDĐ he went through thick and thin with his fellow comrades and was imprisoned in later years. The paintings he did at the dusk of his life were classified as national treasures.

“Khái Hưng was in his fourties, thin and small in stature, but alert and very cheerful. He often joked with me. On busy days, I sometimes brought food to the paper’s office for Bách. But when he was too occupied to eat, Khái Hưng and Bách’s niece and nephew Tường Ánh, Tường Triệu would have a “taste” of the dishes and congratulated the cook. I could not help bursting out in laughter.”

Khái Hưng (born: 1896), the oldest, Nguyễn Tường Bách’s senior by 20 years, he adopted Tường Triệu, Nhất Linh’s son, and named him Trần Khánh Triệu. Khái Hưng was famous with his works Hồn Bướm Mơ Tiên, Nửa Chừng Xuân, Tiêu Sơn Tráng Sĩ… he was one of the leading writers of the Tự Lực Văn Đoàn group. A revolutionary, member of the Đại Việt Dân Chính party, imprisoned by the French, then arrested and assassinated by the Việt Minh in 1947.

“Vũ Hồng Khanh, when we first met, he looked portly, dark skinned, robust, persuasive voice, more of a military man than a politician. At the time, simple in manners, plain in talk, having lived in Yunnan for a long time, he spoke fluent Yunnanese.”

“Xuân Tùng, the plainest of the group. Always slovenly dressed with a water pipe as constant companion. He was rumored to go on frequent secret missions during the French occupation. Constantly in a hurry, as if there were so many things he needed to attend to, he seemed to be incapable of sitting still for long.”

The personalities Bảo Liên met, were depicted by her in a few simple but lively lines that brought out their real characters. Nguyễn Tường Thiết once remarked: years later, when seeing uncle Xuân Tùng again, everybody immediately recognized his “rushed rushed” manner, exactly as described by aunty Bách.The critic Nguyễn Mạnh Trinh, after reading the memoir Nguyễn Tường Bách and I, observed: “through her work I encounter a writer in the person of Hứa Bảo Liên, with her simple literary style, sincere but expressive.”

HONG KONG CONFERENCE

In 1947, in Kunming, Nguyễn Tường Bách received the order from “anh Tam” to attend the Conference in Hong Kong. Right from the start, Nguyễn Tường Bách did not wish to take part in that Conference. He did not support the “Bảo Đại Solution with the conditions imposed by the French” because, in his opinion, it legalized the French invasion. Nevertheless, in compliance with the party’s decision, Nguyễn Tường Bách had to show up to observe the situation and report on the stands of the political parties coming from all corners of the world.

Just as predicted, the Hong Kong Conference hit an impasse due to the blatant divisions among the nationalist groups. Meanwhile, the Việt Minh never stopped their unchanging propaganda accusing “the Hong Kong Conference attendees as traitors and condemned all of them to death in absentia.” [3]

Picture 4a: Former Emperor Bảo Đại, Empress Nam Phương and the Vietnamese politicians at the Hong Kong Conference in 1947 (Nguyễn Tường Tam in the third row, third person from the right). [ORDI document / Oriental Research Development Institute – Viện Nghiên Cứu Phát Triển Phương Đông]

Picture 4b: Vietnamese politicians participants in the Hong Kong Conference 1947 [photo taken in the office of former Emperor Bảo Đại], front row from left, Phan Văn Giáo, Trần Văn Lý, Trần Thành Đạt, Hà Xuân Hải, Nguyễn Hải Thần, Lưu Đức Trung, Trần Quang Vinh, Trương Vĩnh Tống, Nguyễn Văn Tâm, Nguyễn Tường Tam – Nhất Linh and Vũ Kim Thành; second row standing from left, Nguyễn Bảo Toàn, Trần Văn Tuyên, Lâm Ngọc Đường, Cung Giũ Nguyên, Cao Văn Chiểu, Trần Ngọc Liễng, Nguyễn Văn Sâm, Nguyễn Văn Hải, Ngô Xuân Tích, Nghiêm Xuân Việt, Vũ Quốc Hưng, Nguyễn Phước Đáng, Nguyễn Tường Long – Hoàng Đạo. [ORDI document / Oriental Research Development Institute]

MOVING FROM KUNMING TO GUANGZHOU

Beginning of 1948, due to financial constraints, Nguyễn Tường Bách, older brothers Tam, Long and the other comrades decided to move to Bạch Hạc Động, a suburb of Guangzhou – the largest city in Guangdong Province at the time. To go from Bạch Hạc Động to Guangzhou one had to take a boat to cross the Châu Giang River, then walk a long way before arriving.

They moved into two small long-abandoned houses with a low rent of only HK$5. “They led a very austere life, two meals a day prepared by a lady next door. Each meal consisted of a pot of vegetable soup, a small dish of stir fried meat or fish. Brother Tam usually ate noodle due to his stomach problems. Brothers Long and Bách hardly ate regardless of the amount of food being served.

“I still remember after the Hong Kong Conference, Vũ Hồng Khanh, Đỗ Đình Đạo came from different places while Phạm Khải Hoàn arrived from the homeland. They met throughout the week, debated heatedly. In ordinary time they were comrades going through thick and thin together. But when talking business, they felt free to express their personal views, voiced their arguments in order to come to common decisions.

Summer 1948, the wives of brothers Long and Tam came to see them. They brought liveliness and joy to our place. Long’s wife was accompanied by their son Ánh who was about 12. She also took along warm clothes for him. Not long after, brother Tam’s wife and their son Thạch, also about 12, showed up…” [5]

UNEXPECTED MOURNING: HOÀNG ĐẠO’S DEATH

July, 1948, a devastating news, a Vietnamese national unexpectedly died on a train from Hong Kong to Guangzhou. He suddenly slumped down in his seat while reading the newspaper. All rescue attempts proved futile; his body was disembarked at the Thạch Long Rail Station.

The first person who received the news was Hứa Bảo Liên, now Mrs Nguyễn Tường Bách. The newsbearer was the lady owner of a convenience store as well as mail station in Bạch Hạc Động. Hứa Bảo Liên noted:

“When I gave the news to the people at home they were apprehensive but told themselves a lot of Vietnamese bear the last name Nguyễn and we could not be sure if it was brother Long. Throughout the day we were beset with uncertainty and anxiety. The following morning, once more I went to the market. This time, the lady seemed to be waiting for me. Upon seeing me, she immediately said: I was told, the person who passed away on the train was named Nguyễn Phúc Vân (brother Long’s nickname known only to a few). I did not let her finish, dropped the basket, and ran straight home with only one sandal on one foot. At the news, everybody remained speechless but tears flowed down from their eyes … After a brief moment, Bách rushed home and told me: ‘Early next morning, we must all go. However, no one has money and knows how much it costs. Now, you go to Guangzhou and borrow $HKD 500 (about 60 USD, the ongoing exchange rate was 1 USD to 8 HKD), from Miss Binh. If she doesn’t have it then ask her to borrow from someone else for us with the promise we’ll pay back right after we’re done.’ I knew we urgently needed the money. But it was a big sum, equivalent to two taels of gold, I was not sure we could borrow the money.” [5]

Hứa Bảo Liên rushed to the dock, boarded a boat to cross the Châu Giang River, running and walking on the way to the home of her former classmate who was a businesswoman living in the city. She was able to borrow the money to take care of brother Hoàng Đạo’s funeral. This showed how broke the VNQĐD Overseas Office was and the hardship, deprivation their members must face everyday. However, it did not prevent the Việt Minh from spreading the news that Nguyễn Tường Tam had embezzled two million of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ public funds and absconded to China.

Hứa Bảo Liên cotinued:

“The next day, the brothers got up early to be on their way. I had a small child so they advised me to stay home… Two days later, they returned, looking haggard, listless, their eyes all red. There was really nothing more heartrending than having to endure the loss of dear ones while living in exile! I was told by Bách that when they removed the coffin’s lid, in their grief they could not utter a single word, a scene that would remain etched forever in their memory. All the luggage and documents in brother Long’s possession were returned to them without any problem.” [5]

And this is the on-location description Nguyễn Tường Bách, Hoàng Đạo’s younger brother recalled: when we arrived, opened the coffin, his face was swollen and disfigured but we could still recognized it was brother Long thanks to the western style suit he usually wore. Everybody felt sad but brother Tam was the most affected. We could do nothing more than dig a modest grave for brother Hoàng Đạo, plant for the last time a few incense sticks, solemnly place a tombstone at the head of the grave with the inscription:

NGUYỄN TƯỜNG LONG

Vietnamese National

Born 1906*, Died 1948

Repose in peace

[* Hoàng Đạo’s correct year of birth is 1907

the year of the goat Đinh Mùi but listed as 1906 in the birth certificate]

Picture 5: Hoàng Đạo (1907-1948)

One month later, Nguyễn Tường Long’s wife came to visit her husband tomb with their daughter Minh Thu. Her long wailing testified to her deep grief and anguish. After that, she headed straight for Hong Kong and Hứa Bảo Liên returned to Guangzhou. This was also the last time they met.

Nguyễn Tường Bách remembered his older brother with these emotional lines : “In the long journey we trudged side by side, there were so many companions who joined us and fell down. I could never imangine that my dear brother, my mentor from the day I was still a young boy, a talented son of the motherland, a pioneer in the literary movement, a prisoner in the French concentration camp, a down-to-earth person, humble but resolute and uncompromising fighter against the imperialists, dictators, a selfless individual has left us at an unfamiliar railroad station in a foreign land.” [3]

THE ROAD TO NANJING

1948, the nationalist parties overseas stood at a crossroad. To live in regions under French control was tantamount to surrender. On the other hand, to join the maquis would mean complete isolation and possible annihilation by the Việt Minh. In the meantime, the Kuomintang Forces led by Chiang Kai-shek was retreating at all fronts before the Mao Tse-tung’s Red Army. Chiang Kai-shek turned to the Americans for help with no avail.

Facing that predicament, the VNQDĐ leaders decided to send Vũ Hồng Khanh and Nguyễn Tường Bách to Nanking – the still safe bastion of the Chinese Kuomintang to take stock of the situation and plan for future actions. In Nanking, the Vietnamese delegation was able to meet with the important members of the Chinese Kuomintang Secretaria like Vice President Ly Ton Nhan, the second leader after Chiang Kai-shek. He was the reputed General commanding the Route Army 19 that defeated the Japanese at the Battle of Tai'erzhuang. Diplomatically, Ly Ton Nhan expressed his sympathy and support for the Vietnamese struggle against the French

colonialists and promised to refer the matter to the central office to study steps for concrete assistance.

The delegation was used to the promises from KMT officials of all levels. The deteriorating military situation facing Chiang Kai-shek’s Grand Army forced him to think of moving the capital city from Nanking to Guangzhou. The Vietnamese realized plainly they could not expect any help from the Chinese Kuomintang when Chiang Kai-shek’s Grand Army – though more numerous than Mao’s Red Army – was on the verge of collapse.

BROTHER TAM SUFFERING A NERVOUS BREAKDOWN

The looming impasse, the unexpected death of younger brother Hoàng Đạo, plus the change in the youngest brother Nguyễn Tường Bách’s ideology, all contributed to Nguyễn Tường Tam’s depression and faltering health. On top of that his stomach problems rendered him incapable of dealing with the growing critical crisis. The group unanimously agreed to let him leave Quangzhou for Hong Kong for treatment. In Hong Kong, brother Tam lived with comrade Trương Bảo Sơn and his wife Nguyễn Thị Vinh. Under the coaching of Nhất Linh Nguyễn Tường Tam, the two students Nguyễn Thị Vinh and Linh Bảo later became well-known writers of the South (Vietnam).

Picture 6: The rare and last picture taken at Shanghai in 1947 of the three Nguyễn Tường brothers: front row – from left, Trần Quang Vinh, Lưu Đức Trung, Nguyễn Hải Thần, Nguyễn Tường Tam Nhất Linh, Trần Văn Tuyên; second row - from left, Nguyễn Bảo Toàn, Đỗ Đình Đạo, Nguyễn Tường Long Hoàng Đạo, Nguyễn Văn Sâm, Nguyễn Tường Bách Viễn Sơn, Lâm Ngọc Đường. [private collection and annotations by Nguyễn Tường Thiết]

In later days, when talking about Nhất Linh’s death, Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách still recalled brother Tam’s symptoms, starting in 1948, of sleepless nights, sitting alone by himself and sudden bursts of tears without apparent reasons, He diagnosed them as depression.

LOOKING FOR A NEW VENUE: SECEDING FROM THE QUỐC DÂN ĐẢNG PARTY 1949

Events in China unfolded at a rapid pace. The Chinese Kuomintang, the support of VNQDĐ, faced an extremely critical situation. The Red Army widened its assault on the north bank of the Trường Giang River, threatened Nanking and Shanghai, surrounded Hankou. The KMT generals made preparations to withdraw to Taiwan or flee to Hong Kong and the United States.

With the danger of the Red Army advancing into Yunnan, many members of the Vietnamese VNQDĐ had to return home or move to Guandong. “Brother Xuân Tùng who fought in the revolution for so many years arrived from Kunming and expressed his desire to return home. In his opinion it was where the action was. He did not join the communist ranks but also vowed not to cooperate with the French. We bid an amicable goodbye and he wished to see us soon in Vietnam.” [3]

Everybody felt we hit an impasse. “Therefore, I – Nguyễn Tường Bách, and several in our group were determined to search for a new path leading not only to independence for our prople but also a just society free from oppression and exploitation but absolutely neither dictatorial nor proletarian.”

Nguyễn Tường Bách observed with bitterness: “The Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng Party had not only met defeat but also broken into fractions working at cross purposes. A typical case: a number of them operated in the open under the protection of the enemy: the French robbing the party of its just cause and trust from the mass.”

Nguyễn Tường Bách departed for Hong Kong to discuss the “new ideas” with brother Tam and the others. “As for our idea of abandoning the Three Principles of the People, and look for a new approach to overcome the impasse, brother Tam did not say anything specific, neither approving nor opposing our work. It has been his habit never to impose his wishes on others. Probably that’s the reason why he was unable to impose strict discipline among the ranks.” The two of us – Nguyễn Tường Bách and Nguyễn Tường Tam parted ways.

Nguyễn Tường Bách headed back to Guangzhou on the same fateful train route brother Hoàng Đạo took not long ago. “I gave it much thoughts. This is the moment I had to decide my future, a break from the past that may lead to unforeseen difficulties or uncertainties. However, a man, a warrior cannot follow a beaten path, provided he is inspired by the noble cause pertaining to the independence and happiness of the people.” [3]

In Guangzhou, “in heated consultation with the other comrades along with Văn Đạo, a comrade in Gaungzhou, our group came to a common understanding on the following points:

_ Political platform: achieve, on behalf of the people, independence, democracy, liberty, and social equality, moderate capitalism, preserve the interests of the workers and farmers class. Oppose the dictatorship of the proletaria, the brutal exploitation of capitalism. Establish a “socialist society” free of dictatorship similar to the Scandinavian countries’ model.

_ Plan of action: eliminate the colonial regime and the dictatorship of the communist Việt Minh. The main focus is to gradually propagate the idea among the population, promulgate a popular movement to incite step by step a popular uprising and seize power. In principle, during this period, support the resistance of the people.

We formed a new struggle group named “Socialist Revolution”. To avoid any confusion, in March 1949, we decided to secede from the Quốc Dân Đảng Party, while maintaining friendly contacts with it and other anti-French nationalist parties.

DECISION TO STAY AT GUANGZHOU

A new path forward: renounce the Three Principles of the People, secede from the Quốc Dân Đảng Party. The “Cách Mệnh Xã Hội/Socialist Revolution” advocated by Nguyễn Tường Bách lost contact with the homeland. Under those extreme circumstances, the group struggled to publish several issues of the paper “Cách Mệnh Xã Hội”. In the beginning, it was printed in litho form which was very difficult to read. Afterward, it was later switched to typesetting which was more legible and allowed for a larger circulation that included Yunnan, Guangxi, Hong Kong or taken to the homeland by the brothers. Nguyễn Tường Bách himself later remarked that the content in the paper sometimes was inconsistent. Opposing the communists’ dictatorship while supporting the just cause of their fight against the French. Caught between the French and communists but lacking real strength, the future direction espoused by the Cách Mệnh Xã Hội group proved to be ambiguous.

In the meantime, Mao’s Red Army crossed the Yangtze River, threatened Hunan, and Liangguang. The communist guerillas were very active in Guandong itself. The situation was desperate, leaders of the Chinese Kuomintang fled to Taiwan and Hong Kong. Vietnamese expatriates from all over converged on Guangzhou, trying to find a way to Hong Kong. A number of them went back to Vietnam.

Nguyễn Tường Bách wrote:

“The middle months of 1949 witnessed a real turning point in our lives as well as that of Chinese history. The sunny summer days marked the collapse of Chiang Kai-shek’s regime.

“Countless sleepless nights, feverish contemplations, unsettled anxious state of mind. One of those afternoons, I sat waiting for the boat on a section of the Sa Diện River, where warrior Phạm Hồng Thái drowned himself 25 years ago (1924). I had no idea why, on this day I was sitting at that exact same spot?

“I sat for a very long time on the wharf, when I – Nguyễn Tường Bách, got back on my feet my mind was set: I will remain in this land to learn new things while at the same time explore the ways to participate in the fight against the French.”

“Little did I know, that decision completely changed the course of my existence and started me on a long-drawn life in exile under unusual circumstances - even more so than in adventure novels - that eventually landed me on unpredictable shores.” [3]

A MORE THAN 40 YEAR LONG HIBERNATTION

Though my mind was already made up, I still felt apprehensive that I was about to venture into an uncertain future. Hứa Bảo Liên was worried that her husband who went to spend the night at Guangzhou had not come home yet. Nguyễn Tường Bách informed Liên of his decision to stay in China. She agreed with him and told him that no matter how great the danger and challenges, she was willing to face them and wanted to be always by his side especially under the current extraordinary circumstances.

It is noteworthy to mention the very uncommon fact that Hứa Bảo Liên held a French citizenship. When she went to Nam Định to see her father, he handed her a birth certificate showing her French nationality before she travelled to China to attend Yunnan University. Bảo Liên torn up that birth certificate upon learning that Nguyễn Tường Bách has decided to stay in China.

September, 1949, the Red Army advanced to the very city limits of Guandong. The generals of the Kuomintang took flight. The Guangzhou inhabitants felt perplexed and purturbed. It’s not safe to stay at Bạch Hạc Động – on the outskirt of Guangzhou. Amidst that unrest, by coincidence Hứa Bảo Liên met a Chinese friend she knew in Vietnam who was a teacher in Foshan, a small town 20 km from Guangzhou. He offered to recommend Liên to teach at an elementary school there. Mid September 1949, the family comprising of Nguyễn Tường Bách, Hứa Bảo Liên and baby Hứa Lan, their oldest daughter, left their home in Bạch Hạc Động with a heavy heart, the home they shared for almost two years with their comrades who has then dispersed to the four corners of the world.

Nguyễn Tường Bách penned:

“Though beset by sadness, we felt calm and devoid of worry. Moreover, if the situation turned onerous, we could always go to Hong Kong or return to Vietnam. Anyway, I already chose the adventurous path, I had to see it through. The only unimaginable thing was that our journey led us to this temporary station in Foshan – that would eventually last fourty years! Foshan, the Buddha Mountain – certainly an auspicious land … but it was from that place that we witnessed the birth of a totally new China, and experienced the rarest events on this earth.” [3]

In this author’s opinion, the 40 year stay in Foshan could be compared to a “hibernation” time for Nguyễn Tường Bách. From a fervent revolutionary in the decade of the 1940 – 1950, Nguyễn Tường Bách became a country doctor – a Country Symphony, beautiful but sad. Throughout those 40 years, probably Nguyễn Tường Bách was the only Vietnamese who witnessed the various phases of the horrifying storm of blood and tears of the China’s Great Cultural Revolution. Nguyễn Tường Bách recorded those precious and unique experiences in his his book Hồi Ký Hai 54 năm lưu vong / Second Memoir – 54 years in Exile. [3]

Picture 7: A family recital of Nguyễn Tường Bách - Hứa Bảo Liên family in Foshan. At that time (1967), Nguyễn Tường Bách was the head of a large family of 6 children: 5 daughters and 1 son. Nguyễn Tường Bách worked as a country doctor and Hứa Bảo Liên an elementary teacher. [private collection Hứa Bảo Liên]

In 2005, Lawyer Lâm Lễ Trinh asked: “Bách, do you think it was a mistake and waste of time for you to decide to live in China for more than 40 years?” And Nguyễn Tường Bách asserted: “That decision was not wrong but unfortunate. From this point in time, I want to look ahead to the future.”

THE DEATH OF NHẤT LINH 1963

“July 1948, the sudden news of brother Hoàng Đạo’s death on the train from Hong Kong to Guangzhou broke the heart of every [Vietnamese] expatriate. In the same month of July but in 1963, I unexpectedly received a telegram from Shanghai sent by Văn – Vũ Đức Văn who is now teaching at the Ngoại Ngữ Học Viện/ Foreign Language Institute. Who could expect it, the telegram started like this: ‘I received the sad news that Nhất Linh Nguyễn Tường Tam has passed away.’ Văn obtained the news from an article on the paper L’Humanité published in Paris by the French Communist Party. It said: ‘Author, politician Nguyễn Tường Tam who was involved in a political trial has committed suicide. He served as Foreign Minister in the National Union Government of Vietnam in 1946…’

“I stayed speechless at the unexpected news, unable to control the pain surging inside. How could it be so? A dear brother, a close companion in a literary and revolutionary journey, sharing together so many moments of gladness and griefs, during sunny and rainy days, wanderers in life, blood relatives but more than that companions in life and death, still harboring the hope to meet each other again some day in the motherland – now I’ve lost a dear brother, gifted, a talented son of the land, unable to see him for the last time in the country.” [3]

Also, in the interview with Lawyer Lâm Lễ Trinh (2005), Nguyễn Tường Bách – after a 17 year stay in the United States, stated: “Brother Nhất Linh decided to put an end to his life. This way of handling things, deep down, I do not agree with.” Nguyễn Tường Bách then clarified himself and believed the choice made by Nhất Linh was unfortunate and negative. Nhất Linh could have easily gone overseas, say to Cambodia, when the situation changed he could go back, brother Tam still had a lot to offer, especially in the field of literature and culture. “I heard a lot of people attended his funeral, the mass thronged the streets to say farewell to a gifted son of the people. Nevertheless, no matter how big, how solemn the funeral, it does not mean much when a person has left this world.” [6]

Picture 8: Portrait of Nhất Linh

Nguyễn Tường Tam (1905* – 1963)

by artist Nguyễn Gia Trí

[* Nhất Linh’s correct year of birth is 1906,

Bính Ngọ the year of the horse, in the birth certificate it is listed as 1905]

HOMECOMING TO VIETNAM 1977

September 1977, exactly 30 years on the day he left the homeland (1947 – 1977), 14 years after brother Tam’s death, 2 years after the Communist North conquered the South, Nguyễn Tường Bách and his youngest son Tường Kiên, still a minor, embarked on a trip to visit Vietnam. [Hứa Bảo Liên also applied to go along but was denied, because the authorities feared if the whole family left the country they will not return]. Father and son headed from Foshan to Hunan to take the express train Moscow – Beijin – Hanoi, to visit Vietnam.

Near the border, they had to transfer from a comfortable sleeper wagon of a train running on a track with the international standard width of 1.5 m (1.435 mm) to a Vietnamese ancient rail system with a track width of only 1.000 mm, dating from the French colonial period (1904-1910), narrow, old wagons; the Vietnamese crew small in stature and sloppily dressed. The first impression of an impoverished Communist Vietnam – So sad.

Then the rickety Vietnamese train crossed the Nam Quan Pass – now renamed Hữu Nghị Quan/Friendship Pass, this place has witnessed many a battle with the conquerors from the North during their invasions of our fatherland. The very next stop is the Đồng Đăng Station, Nguyễn Tường Bách still remembered this proverb that is associated with it:

Đồng Đăng is known for Kỳ Lừa Street

The lady Tô Thị, the pagoda Tam Thanh

The train made a very short stop, “I stepped into the station platform, to have my feet touch the native land after thirty years.” The train again rolled on the track, green grass all around due to lack of maintenance. It slowly passed familiar locations, Lạng Sơn then Bắc Giang, we could see poverty everywhere, abject poverty. Then the train noisily traversed an iron bridge – the Thăng Long Bridge, looking down I saw the Red River flowing turbulently like always. At last, we arrived at the Hàng Cỏ Station. Phố Ga did not change the slightest, tiny and drab.

Hà Nội still kept its old self – older than the French colonial period that dated back for more than half a century. Poverty was the first impression that characterized my first days in Hanoi. I succeeded in contacting a number of old friends I had not seen for quite a long time. The circumstances have changed greatly but their hearts haven’t – still open and sincere. Their families had one thing in common: poverty, extreme poverty – even though they worked as civil servants or medical doctors.

I also met an old colleague who was now institute head. After so many years of absence, in a subdued sad tone he observed: “Stagnation, stagnation … they have never accomplished anything that counts!” then in privacy and all sincerity, he advised me not to return to the country.

“I also felt down hearted. Why so much misery, such doldrums? Because of the war? But why are we fighting while we’re in such utterly desperate conditions?”

However, the most moving event was when Nguyễn Tường Bách paid a visit to the Yên Phụ dike, the same communal house, but many of the tiles on the pavement were worn out or broken. The same familiar path that has endeared itself to his loved ones throughout the years.

“Out of the blue, the image of brother Thạch Lam, tall, thin, a beret on his head, walking slowly on this path on his way home, appeared before my eyes. And so many others. Where are those people now?” [3]

The Yên Phụ road holds a long association with the members of the Nguyễn Tường family, and their friends: Khái Hưng, Thế Lữ, Đoàn Phú Tứ, Huyền Kiêu, Đinh Hùng, Nguyễn Gia Trí, Vũ Hoàng Chương, Xuân Diệu… they all frequented that thatch house. Those people of old, where have they gone now?

I had to go see the house at 80 Quan Thánh Street, the office of the papers Phong Hoá, Ngày Nay, Việt Nam. In the old days, it could be recognized easily, at the corner of the street with a balcony protected by an iron fence. Now, everything looked different, it took great pain to find the front entrance and the old plate showing the street address number 80.

“Grief and changes. Overwhelmed, I stood there staring at the place for a brief moment. The people living next door were probably thinking we were looking for an address. Unbeknownst to them, we were the very owners of that house, thirty years ago, and so many strange events have taken place since.” [3]

So very moving. The readers are inexorably reminded of the poem by Hạ Tri Chương translated by Trần Từ Mai:

Leaving young, returning old

The speech unchanged, hair turned grey

Looking surprised, the kid asks with a smile:

Where do you come from, you have just arrived?

Hanoi 30 years later, the everyday life was exceedingly harsh and poverty-stricken while the cultural life did not fare any better. Only the state newspapers were allowed: Nhân Dân, Quân đội Nhân dân, Hà Nội Mới, covered with slogans and their content pared to the bone.

Nguyễn Tường Bách knew full well that during his visit he was constantly been watched by the security police. Several letters coming fom the South urged him to come for a reunion and visit the tombs of brother Tam, his wife and other members of the Nguyễn Tường family. However, he was still waiting for his application to travel to be approved. Finally, the answer came with the explanation: “considering the situation in the South is still unsettled, the security still not good, the authorities suggest …” The message definitively means Nguyễn Tường Bách’s application to go south was denied.

He was only allowed to visit Hanoi and a few other cities in the North like Nam Định, Bắc Giang… The two-month permit was drawing to an end. It’s time for Nguyễn Tường Bách to say his farewell to Vietnam. He took the same train at the Hàng Cỏ Station, but this time heading North, in the opposite direction, on the Long Biên Bridge. Hanoi was slowly retreating to the rear, only an undescribable sadness lingered on in his soul.

LE REPOS DU GUERRIER – THE END OF THE STORM

The visit to Vietnam 1977, after 30 years, only left a bitter aftertaste. Back in Foshan, Nguyễn Tường Bách worked for three more years eventhough it was past his retirement age. In 1980, this country doctor officialy retired at the age of 64. The situation turned tense as a result of the conflict at the Sino-Vietnam borders. The Chinese living in Vietnam flocked to China. Among them was a young Chinese named Lý Trung Nhân. He graduated from the Bách Khoa University in Hanoi and his father was Dr. Lý Hồng Chương, a classmate of Nguyễn Tường Bách at the Medical School. The young man was welcomed into Nguyễn Tường Bách’s family then became his son-in-law. Under the sponshorship of his mother, Lý Trung Nhân emigrated to the United States with his wife Hứa Anh, the fourth daughter of Dr. Bách. Afterward, Bách’s fifth daughter was granted permission to travel to America to donate blood to save the life of her sister who suffered from leukemia. A miracle happened, the procedure was successful. The two daughters of the the couple Nguyễn Tường Bách - Hứa Bảo Liên later became naturalized American citizens and petitioned for their parents to be reunited with them in the United States.

Picture 9: Nguyễn Tường Lưu traveled from Australia to see Uncle Bẩy in Foshan, Guandong Province. The following year (1986) his younger brother Nguyễn Tường Vũ visited Uncle Seven from Canada (Lưu and Vũ were the sons of Nguyễn Tường Thụy, the oldest of the Nguyễn Tường brothers). The photo was taken with the two of them standing in front of Bách’s modest house with an old bicycle leaning against the wall and clothes hung out to dry. The scene was reminiscent of the Bàn Cờ district in Saigon of old. The joy of seeing his uncle did not prevent Lưu from being profoundly moved by his uncle’s austere and humble way of life. [photo by Nguyễn Tường Lưu, Foshan 1986]

FAREWELL TO CHINA, WELCOME TO AMERICA

In 1988, after a stay of 49 years Nguyễn Tường Bách and Hứa Bảo Liên left China. For the revolutionay Nguyễn Tường Bách it was a waking up from his “hibernation”. The couple set foot in America when he was in his seventies but with a heart of a 30 year old youth who left Lào Cai to go through the Hà Khẩu pass and begin his adventure in China. Now at the age of 72, starting anew in another continent, Nguyễn Tường Bách felt he was fully in his elements and enthusiastically started a new endeavor of over 20 years with several projects in mind: Establish “Uỷ Ban Điều Hợp Các Tổ Chức Tranh Đấu cho Việt Nam Tự Do/ Coordinating Committee for the Organizations Fighting for a Free Vietnam”, and “Mặt Trận Dân Tộc Dân Chủ Việt Nam/ Popular Front for Democracy in Vietnam”, and the most serious one “Hoạt Động Nhân Quyền và Dân Chủ cho Việt Nam/ Advocacy for Human Rights and Democracy for Vietnam” working in tandem with “Human Rights Network.”

REINTRODUCTION TO LITERARY LIFE

Hứa Bảo Liên noted: “Bách often said “medicine is a profession, revolution a cause, but literature my main calling.” During retirement in Foshan, he picked up the pen to write feverishly. He did it with youthful vigor. Decades have gone by as if it was just yesterday. Pen in hand, he immersed himself in his youthful past with its beautiful sceneries, idyllic student years, fervent time devoted to journalism or writing, periods of hardship, peril, life and death moments in the battlefields and ordeals of a life in exile.

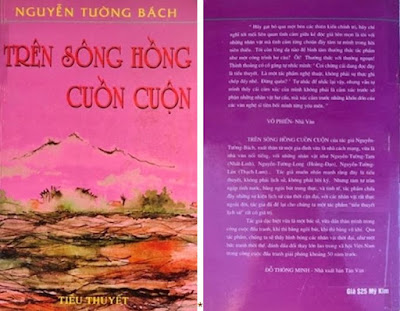

His first memoir Việt Nam Những Ngày Lịch Sử published in Canada, was written in the short period of six months. Also in 1980, he finished the political commentary, “Một vài ý kiến về vấn đề Việt Nam/ Ideas on the Issues Facing Vietnam” and sent it abroad under the pen name Viễn Sơn. Surprisingly it was well received and helped bring about the consolidation of several organizations. His next work was a saga. He was really enthused. Hứa Bảo Liên typed each chapter at a time. If he was not happy with a chapter he just finished, in the basket it went! When he was done with the manuscript, the two discussed about the book title. They finally chose Trên Sông Hồng Cuồn Cuộn.

Never a literary critic, Hứa Bảo Liên nevertheless offered this pertinent remark: “This book – Is Trên Sông Hồng Cuồn Cuộn a saga or drama of our time? It is a saga of those who were devoted to the struggle against colonialism and dictatorship – but also a huge drama in the history of the Vietnamese people and the pain that engulfed the entire country when they were met with defeat.” [5]

Picture 10a: The first pages of the manuscript of the saga Trên Sông Hồng Cuồn Cuộn by Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách, finished in the Fall of 1982 in Foshan, Guandong Province. [Private collection: Nguyễn Tường Giang]

Picture 10b: Book cover for the saga Trên Sông Hồng Cuồn Cuộn by Nguyễn Tường Bách, 655 pages. The manuscript was written after his retirement, typed by Hứa Bảo Liên and finished in Foshan, Quảng Đông Province. Published by Tân Văn – Đỗ Thông Minh in 1995. [private collection: Phạm Lệ Hương]

Picture 11: Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách and author Võ Phiến – Võ Phiến is 9 years younger than Nguyễn Tường Bách, they met in May, 1995 at Võ Phiến’s home in Los Angeles; Võ Phiến wrote the foreword for “Cảm xúc khi đọc cuốn Trên Sông Hồng Cuồn Cuộn”, Both of them are no longer with us. [private collection: Viễn Phố]

Picture 12: Book covers of the works by Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách published overseas; left: Việt Nam Những Ngày Lịch Sử, published by Nhóm Nghiên cứu Sử Địa, Canada 1980; center: Việt Nam Một Thế Kỷ Qua Hồi Ký, Cuốn Một (1916-1946), Thạch Ngữ Publishing House 1998; right: Việt Nam Một Thế Kỷ Qua Hồi Ký, Cuốn Hai (Trung Quốc 1946-1988, Hoa Kỳ 1988-2000) Thạch Ngữ Publishing House 2000. [private collection: Trần Huy Bích]

WORK BY HỨA BẢO LIÊN

Nguyễn Tường Bách và Tôi, is the name of the outstanding family memoir by Hứa Bảo Liên, finished in 1996 - 245 pages, self published in 2005.

Picture 13: left, front cover of family memoir Nguyễn Tường Bách và Tôi, by Hứa Bảo Liên published in the United States in 2005; center, dedication by the writer to this author; right, back cover with the excerpt from the notes of Mekong Dòng Sông Nghẽn Mạch/Mekong, the Occluding River by Ngô Thế Vinh on his visit to Yunnan University. [private collection: Ngô Thế Vinh]

Picture 14: A visit with Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách – Hứa Bảo Liên family, from left sitting row: Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách, Mrs Nguyễn Tường Bách Hứa Bảo Liên, Vân Loan wife of Nguyễn Nhã; standing row: Ngô Thế Vinh, Nguyễn Nhã, Trần Huy Bích. [Picture taken 8/24/2004, private collection: Ngô Thế Vinh]

Picture 15: Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách - Hứa Bảo Liên, from left, Nguyễn Tường Giang, Nguyễn Tường Thiết and wife Nguyễn Thái Vân. [private collection: Nguyễn Tường Giang]

A PERSONAL NOTE

Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách was 25 years my senior, a gap of a quarter of a century. On top of that, his worldliness, experience and contribution to the country were in a class by themselves. In the medical field, Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách belonged to the class of 1944 of the Hanoi Medical School. His classmates who chose to go into an academic career ended up being my professors at the Saigon Medical School. The son of writer Thạch Lam, Nguyễn Tường Giang my classmate (class of 1968) was Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách’s nephew. In spite of all that difference, uncle Bách always treated me with humility and magnanimity. In our interactions, uncle Bách at all times addressed me as “Doctor”... Furthermore, uncle Bách was a veteran journalist, a writer of the Tự Lực Văn Đoàn whose works by Nhất Linh, Khái Hưng, Hoàng Đạo, Thạch Lam… were my close companions in my youth – from the 1950s in Hanoi then in Saigon. In the 1990s, by coincidence, I get acquainted with his two works Hồi Ký Việt Nam Một Thế Kỷ Qua I & II, particularly the novel Trên Sông Hồng Cuồn Cuộn. He wrote all those books during his retirement. After reading them, I hold him in high esteem and feel closer to him. Uncle Nguyễn Tường Bách wrote about the Red River, I about the Mekong. He read my works with interest. In a letter he addressed to me on 8.18.2004, a heart to heart exchange between two like-minded souls, a long time companion, a letter both private and public – the author would like to share what is public with the readers – in particular the young ones.

Picture 16: Handwritten letter by Dr. Nguyễn Tường Bách to Ngô Thế Vinh dated August 18, 2004. [private collection: Ngô Thế Vinh]

Dear Dr. Ngô Thế Vinh,

… With a high minded objective and an outstanding penmanship, the book inevitably will be well received by everybody and create a strong impact among the public both inside and outside the country. I strongly look forward to see you doctor so we can talk. How to raise the level of artistic attainments in Vietnam is synonym to propagating the [people’s] faith in the notion of freedom, democracy and human rights for the Vietnamese and to a certain extent in the progress of humanity. I think, those works of ours will not only help our people but, in our days, will also contribute our small part to that trend. If we make an extra effort, we will certainly achieve good results hand in hand with a great number of Vietnamese who are living in exile…

Sincerely,

Nguyễn Tường Bách, 8/2004

NGÔ THẾ VINH

Little Saigon 1988 – California 2021

Reference:

- Nguyễn Tường Bách. Việt Nam Những Ngày Lịch Sử. Tủ sách tài liệu lịch sử. Nhóm Nghiên Cứu Sử Địa xuất bản, Montréal 1981

- Nguyễn Tường Bách. Việt Nam Một Thế Kỷ Qua. Hồi Ký cuốn Một, 1916-1946. Nxb Thạch Ngữ 1998

- Nguyễn Tường Bách. Việt Nam Một Thế Kỷ Qua. Hồi Ký cuốn Hai, Trung Quốc 1946-1988, Hoa Kỳ 1988-2000. Nxb Thạch Ngữ 2000

- Nguyễn Tường Bách. Trên Sông Hồng Cuồn Cuộn. Tiểu thuyết, Nxb Tân Văn 1995

- Hứa Bảo Liên. Nguyễn Tường Bách và Tôi. Hồi ký gia đình. Tác giả tự xuất bản 2005.

- Mạn đàm lịch sử với DR. Nguyễn Tường Bách, Người em út trong gia đình Tự Lực Văn Đoàn. LS Lâm Lễ Trinh thực hiện 24.09.2005